There are concepts that, while seemingly abstract, possess a profound and often insidious power to shape our lives, our societies, and the very future of human liberty: Totalitarianism, Authoritarianism, and Extremism. These are not mere political labels; they are pathologies of power, each representing a regression from the nuanced, individual-centric flourishing that defines true civilization.

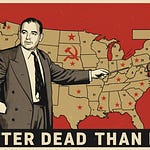

Let us begin with Extremism. What is it, at its core? It is, as I see it, the inability to tolerate difference. It is the fervent, often zealous, conviction that there is but one voice, one truth, one correct path to be permitted, and all others must be silenced or eradicated. Consider the passionate advocate, utterly convinced of their singular truth. While passion can fuel progress, when it metastasizes into the belief that their truth is the only truth, and that all deviation is heresy, then we witness the birth of extremism.

I am a skeptic. I believe truth exists, but it does not reside solely within the domain of secular human beings, nor can any single individual or group claim its exclusive dominion. A philosophical inquiry into epistemology reveals a myriad of pathways to understanding. To assume one's own beliefs are universally and perpetually true is a dangerous hubris. Extremism, in this light, is the most perilous form of collectivism, It is a mindset that cannot abide the tiniest divergence, seeking either to coerce assimilation or to utterly annihilate dissent.

From extremism, we turn to authoritarianism and totalitarianism, systems that embody this collective impulse at the governmental level.

Totalitarianism, in its most chilling form, seeks total control. It is a system of governance that infiltrates every conceivable aspect of human existence – what we wear, what we do, what we see, what we hear. It is not merely a restriction of freedom, but an absolute subjugation of the individual to the state, a relentless flattening of human experience into a singular, state-sanctioned mold. Every private corner of life, every personal choice, becomes a matter of public decree, enforced by the pervasive hand of the ruling power.

Authoritarianism, while perhaps less all-encompassing, is no less dangerous in its implications. It usurps the domain of right versus wrong, wresting it from the individual and placing it in the hands of those in positions of power. Herein lies a critical distinction: the difference between truth and falsehood, and right and wrong. My preference for a certain food, your aesthetic choice – these are matters of individual taste, not universal judgment. Yet, under an authoritarian regime, such personal preferences can be elevated to matters of "right" or "wrong," stripping away individual autonomy and fostering a culture of compliance.

The slippery slope here is terrifyingly steep. When matters of personal choice become matters of right and wrong, they can then be transmuted into matters of truth itself. Those holding differing beliefs, those practicing alternative ways of life, are then deemed "untrue," "unhuman." This dehumanization is the fertile ground from which the most horrific atrocities spring, fundamentally altering how we perceive and treat our fellow human beings.

The mechanics of control, particularly in politics, are deceptively simple: how a small cohort can manipulate a vast populace into compliance, even into serving their narrow interests. Often, it's not brute force alone. It is the cultivation of fear, the narrative that the "weak" must seek protection from a "strongman" or an omnipotent state. Yet, the stark reality is often the inverse: the collective, driven by fear and dependency, becomes the unwitting bulwark for the very "strongmen" who exploit their anxieties.

Consider the role of Ideology and Identity. These are intimately intertwined. What we believe often defines who we are. Contemporary politics is rife with "identity politics," just as the 19th century saw "class struggle." These are attempts to categorize, to group individuals based on shared characteristics or economic status, and then, crucially, to antagonize these groups against one another. It becomes a simplistic "we versus them" narrative, obliterating the rich tapestry of individual identity.

But each of us is more than a member of a single group. We are, at once, independent individuals and members of myriad associations: family, profession, hobbies, language, shared geography. The critical question for a free society is where we draw the boundary between our individuality and the rest of the world. It is not an antagonistic relationship; it is not "I against the world." Rather, it is "I, existing as a complete individual, also belonging to diverse groups that may cooperate or conflict." The danger arises when totalitarian and authoritarian regimes, and extremist organizations, forbid this multiplicity of identity, seeking to flatten complexity into a simple, fanatical "we versus them."

So, how do we safeguard against such insidious forces? The answer lies not merely in the ritual of elections, though they serve the vital purpose of ensuring no one clings to power indefinitely. Democracy is far more profound than mere electoral politics. It is, first and foremost, about the respect for differences. We must accept that in a free and open society, disagreement is not merely inevitable, but essential. The challenge lies in where we draw the boundaries of this disagreement. If a matter does not involve us, if it does not infringe upon our fundamental rights, it is simply not our business to dictate the choices of others. This is the essence of subsidiarity: that power and decision-making should reside at the level closest to the individual, wherever possible and necessary.

Beyond elections and subsidiarity, the true bastions of a democratic society are:

Firstly, free speech absolutism. There will always be speech we deem hateful or foolish. But once we open the Pandora's Box of censorship, we embark upon a perilous slippery slope, where more and more ideas become forbidden, and the very marketplace of thought is choked. We must tolerate speech we disagree with, for the alternative is intellectual tyranny.

Secondly, the free market. Believe it or not, the financial market, in all its chaotic glory, is often the most potent check on governmental overreach. Governments, particularly modern ones, are deeply dependent on financial markets for public financing. Without this lifeblood, ruling coalitions falter, and even the most tyrannical aspirations cannot be sustained. A free market, therefore, is not merely a means to accumulate wealth, but a crucial bulwark against unchecked state power.

Thirdly, and intrinsically linked, is an independent judiciary. A functioning free market, built on competition and cooperation, demands an impartial arbiter of disputes, particularly commercial ones. A judiciary free from political interference is the very avatar of fairness and predictability, allowing the complex dance of commerce and innovation to flourish.

Finally, and perhaps most profoundly, lies the cultivation of civil society. This is not a government program or a political party; it is a state of mind. It is when individuals, unbidden and uncoerced, ask themselves: "What can I do? What can we, voluntarily, do to make the world a better place?" It is a psychological state of self-belief, a rejection of the culture of dependency that leads societies to become subservient to the state. We must believe in ourselves, in our neighbors, and in the power of voluntary action to mend, to build, and to uplift.

Young people today face immense anxieties, particularly in a world transformed by economic and technological shifts that displace traditional certainties. But the government is not a savior; it can, indeed, be the very source of the problem. Fear, whether among the young or reflected in the media, can easily drive us into the arms of "strongmen" – figures who are not truly strong, but rather exploit our anxieties to fortify their own regimes.

True civilization is built on individuals who believe in themselves, who resist the psychological urge to surrender their autonomy to external powers. It is a continuous act of self-reliance, of voluntary engagement, and of a steadfast commitment to the values of liberty, skepticism, and the tolerance of difference. Let us embrace these principles, for they are our most powerful defenses against the encroaching shadows of totalitarianism, authoritarianism, and extremism.