It has been some time since the last update.

The seismic shifts following the events of early 2020 have left many feeling adrift. Subsequently, the trade war destabilized markets. The push for deglobalization is a worrying retreat from the principles of comparative advantage and global cooperation that have historically driven prosperity.

Yet, from a historical and free-market perspective, perhaps we should have anticipated some of this.

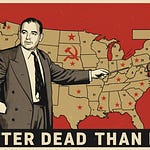

Social discontent is perennial. The siren call to employ governmental coercion never truly fades. These impulses intensify during periods of rapid technological and societal change, as anxieties about individual circumstances rise. The working class often blames globalization for job losses, failing to recognize that these very forces of free trade have expanded access to a higher standard of living. Similarly, the fear of technological unemployment, while understandable, overlooks the creation of new opportunities. This climate of uncertainty bears a striking resemblance to the populist movements of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, where similar anxieties fueled demands for protectionist policies and increased state control, at the expense of peace and liberty.

The transition from the fractured and belligerent nationalism of the early 20th century to the rules-based system of the post-World War II era resulted from deliberate efforts to build international institutions – such as the United Nations, the Bretton Woods system, and later the World Trade Organization. In many ways, the past seventy-odd years have represented a triumph of core liberal ideals on a global scale: the emphasis on free trade, peaceful resolution of disputes, and the rule of law instead of the law of the jungle.

In the optimistic aftermath of the Cold War during the 1990s, a sense of finality, an "end of history," permeated intellectual discourse, with the triumph of liberal democracy seemingly assured. Nevertheless, this perspective significantly downplayed the enduring and often insurmountable role of geopolitics in shaping the destinies of nations. The underlying dynamics of power, competition, and national interest were never fully extinguished by ideological victory alone.

Rules-based systems, for all their merits, remain inherently fragile. Their efficacy hinges on the adherence of even the most powerful nations to the core tenets of classical liberalism, particularly the safeguarding of individual liberty. When these foundational principles are compromised by leading states – as witnessed, for example, when the American government itself infringes upon personal freedoms – the very legitimacy and stability of the international order are undermined.

The aftermath of the 9/11 terrorist attacks marked a significant turning point. The perceived exigencies of national security led the United States to increasingly curtail personal liberties in ways that would have been unthinkable just a decade prior. Surveillance programs expanded, due process was questioned, and the very definition of individual freedom seemed to contract under the weight of fear.

The Global Financial Crisis of 2008 further eroded faith in the principles of free markets and limited government intervention. Government bailouts across the developed world signaled a decisive shift towards greater state involvement in the economy. This interventionist turn further weakened the ideological consistency of the prevailing international order.

This weakening of the ideological foundations of the liberal international order created a vacuum, which China, with its rapidly growing economic and geopolitical influence, has been increasingly eager to fill.

Rather than adhering to the set of broadly free-market economic policies championed by the USA and international financial institutions for decades (often termed the "Washington Consensus"), China has promoted an alternative vision often termed the "Beijing Consensus." The Beijing Consensus, while not always explicitly defined, generally emphasizes state-led economic development, authoritarian political control, and a focus on national sovereignty and non-interference in the internal affairs of other nations. China’s growing economic power, fueled by its blend of state capitalism and export-oriented growth, has allowed it to project its influence and forge partnerships with nations.

As an authoritarian regime, the Chinese Communist Party’s motivations extend beyond mere economic development; a significant geopolitical agenda is at play. The Belt and Road Initiative, in part, aims to cultivate a bloc of nations that are more aligned with China’s authoritarian model of governance, fostering a geopolitical sphere of influence composed of similarly structured regimes.

From this perspective, the optimism surrounding the end of the Cold War in the 1990s, with its perceived triumph of liberalism, may have been premature. While the Soviet Union collapsed, the underlying currents of geopolitical tension never truly vanished. As great power competition intensifies and different ideological blocs solidify, nations may increasingly turn inward, emphasizing national identity and security in response to perceived external pressures and the shifting balance of power.

The COVID-19 crisis, erupting in early 2020, served as another powerful accelerant to the trends we've been discussing. The pandemic and the subsequent global response further fueled discontent amongst populations worldwide and significantly eroded trust in established institutions, both domestic and international. When people feel that traditional authorities – whether political, scientific, or economic – have failed them, they become more susceptible to simplistic narratives and charismatic leaders promising radical change.

This erosion of trust in institutions created a fertile ground for populist sentiments to take root and flourish. As Eric Hoffer observed in The True Believer, "Mass movements can rise and spread without belief in a God, but never without belief in a devil." Subsequent waves of crises since the 9/11 terrorist attacks have generated widespread anxiety and a sense of societal breakdown, inadvertently creating fertile ground for the identification of such "devils." Whether it was a virus, specific social groups, or perceived institutional failures, these crises provided readily available targets for blame and fueled the kind of collective animosity that often underpins populist movements.

Another, perhaps less conventionally discussed, episode during the COVID-19 crisis that illuminated the rising tide of populist sentiment and the erosion of trust in established financial institutions was the meme-stock frenzy, exemplified by the dramatic GameStop saga. Fueled by hype and a populist call to arms orchestrated by Reddit users on platforms like r/WallStreetBets, this movement saw a surge of individual investors banding together to challenge institutional investors – specifically hedge funds that had bet against these companies.

The narrative that emerged was one of a David-versus-Goliath battle: ordinary retail investors uniting to defeat the perceived "corrupt elite" of Wall Street. This resonated deeply with a population already feeling disenfranchised and distrustful of traditional financial systems in the wake of the 2008 crisis and the economic uncertainties of the pandemic. The call to "arm" oneself with stock purchases to inflict financial pain on institutional investors became a form of populist rebellion, a way for the "common person" to strike back against a system they felt was rigged against them.

As we consider the trajectory of these populist movements, Eric Hoffer's framework in The True Believer offers further insight: "A movement is pioneered by men of words, materialized by fanatics and consolidated by men of action." The intense fervor of populist movements, often driven by rhetoric, will eventually subside as the limitations of simplistic solutions become apparent and the "men of words" exhaust themselves.

However, this does not mean the end to societal discontent. Just as one wave recedes, another is brewing. History rarely progresses in a straight line. It is a tapestry woven with conflicting views and values, marked by periods of both advancement and regression. New forms and flavors of populism, fueled by different grievances, will emerge.

It is not the absence of conflict, nor the guarantee of immediate consensus, that defines a resilient society. But rather its ability for diverse perspectives to contend, to be scrutinized, and to evolve through free exchange remains the most reliable compass. As old certainties crumble and new anxieties emerge, the seeds of progress, however unconventional or challenging in their inception, will take root and shape the world to come, emerging from the cacophony of competing voices.